Crocs! Are they back in style? Or did they never go away?

Either way, they’re today’s sponsor! Crocs!

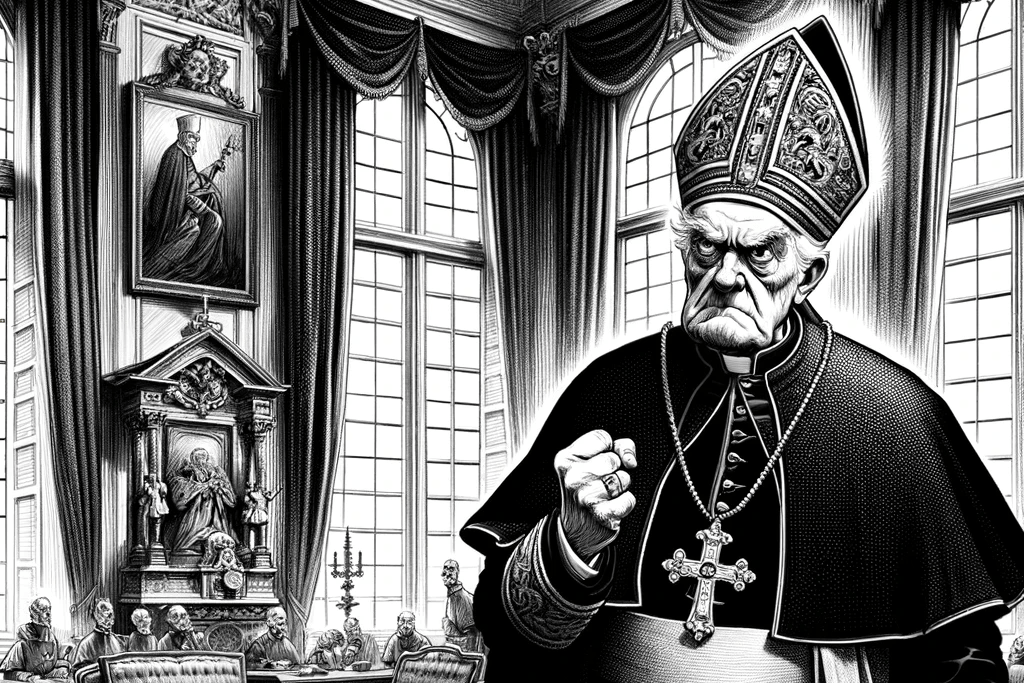

READING, February 13th, 1824 — In the bustling borough of Reading, a matter of grave concern has recently unfurled, reflecting the perennial struggle between the arm of regulation and the spirit of commerce. On the sixth day of February, an assemblage, marked by both solemnity and a hint of theatricality, convened within the esteemed confines of the Council Chamber. Here, the fates of Mr. Adams and Mr. Tilley, proprietors of retail breweries, were to be deliberated upon under the austere gaze of the law, specifically the act of 35 Geo. III. c. 113, which proscribes the sale of beer by retail without due licensure.

Presiding over this convocation were W. Andrews, Esq., the Mayor, and I. Austwick, Esq., an alderman of notable repute, both of whom found themselves entangled in a narrative that transcends the immediate concerns of licensing. The allegations against these brewers have ignited a broader discourse on the role of regulatory oversight in an economy that thrives on the industrious pursuits of its citizens.

The legal skirmish unfolded with Mr. Platt, an advocate for the prosecution, pitted against Mr. Talfourd, who stood in defense of the accused. A preliminary objection raised by Mr. Talfourd, questioning the legitimacy of the proceedings on grounds that they were not initiated by the Excise or the Attorney-General, was briskly dismissed by the Mayor. This judicial episode was not merely a dispute over licenses; it became a platform for airing grievances and casting aspersions on the integrity of the magistracy, a theme all too common in the annals of public administration.

The defense’s argument, articulated with both eloquence and a palpable sense of urgency by Mr. Talfourd, ventured beyond the narrow confines of legal statutes to question the very essence of the legislation under scrutiny. He posited that the 35th of Geo. III., now seemingly antiquated, was effectively superseded by subsequent enactments, notably the 48th of Geo. III., thereby rendering the current prosecutions moot.

The case against Mr. Adams and Mr. Tilley is emblematic of a larger contestation between the forces of tradition and the imperatives of modern commerce. It epitomizes the challenges faced by small-scale entrepreneurs navigating the labyrinthine corridors of regulatory frameworks, which, though designed to safeguard public welfare, often ensnare those it intends to protect.

In Brighton, a parallel narrative unfolded as Mr. Wm. Bush, a retail brewer of some renown, found himself ensnared by the statutes governing the sale of beer. Here too, the magistrates, Sir David Scott and J. W. Cripps, Esq., were compelled to adjudicate matters that straddle the delicate balance between regulation and entrepreneurship.

These episodes, while seemingly isolated, are microcosms of a broader societal debate on the role of government in regulating economic activity. They underscore the need for a regulatory regime that accommodates the dynamism of commerce while upholding the principles of fairness and public good.

As observers of these developments, we are reminded of the immutable truth that the health of a nation’s economy is inextricably linked to the freedom and fairness with which its entrepreneurs are allowed to operate. It behooves the custodians of our laws to ensure that regulations serve not as shackles but as safeguards, enabling the unfettered flow of enterprise that is the lifeblood of progress.

In the year 1824, as we stand on the cusp of a new era of industrial and commercial expansion, the saga of Mr. Adams, Mr. Tilley, and Mr. Bush serves as a poignant reminder of the enduring tension between the letter of the law and the spirit of entrepreneurship. It is a tension that must be navigated with both wisdom and foresight if we are to foster an environment in which commerce can flourish, unburdened by the undue weight of regulatory overreach.

⁂

The content on this website is for entertainment purposes only.

Much of it has not been thoroughly reviewed by humans,

although we do get a blast from reading it ourselves.

But it should absolutely not be cited

as a source for anything other than itself.

We use OpenAI’s GPT-4 API to extract text

from the public-domain archive of The Times,

and rewrite this to contemporary standards.

Graphics are also largely AI-generated.

This website is supported by advertising and donations!

Please consider supporting today’s sponsor,

Crocs, by clicking here to learn more.

Please also consider making a donation here—

we get so excited every time we hear the bell ding,

and there’s no donation too small!

Leave a comment